He'd be here soon, demanding his conjugal rights. A quick toss, then off to his club, while she fretted over bursting with another baby. She'd sneak a drink of wormwood or pennyroyal, hopefully to discourage any breeding.

She peeled off her mouseskin eyebrows; removed her bodice, then her skirt, the underskirt, and oh, the petticoats, dropped them in a pile on the floor. Garters untied, stockings rolled down. No drawers in freezing England; rumor has it they may wear them in France and Spain. Stays unlaced, easier with a maid. The silly girl never attended to her duties. Panniers untied, discarded. Shift slipped off--so stiff with perspiration, the garment could stand on its own. She scratched at her skin, bedbugs from the bed last night.

The wig! She tugged at the fake hair entwined with her own. A wooden ship fell on the floor with a few silk flowers. Where was that maid? She grabbed the hook and stuck it through the wig to scratch her itchy scalp. To preserve the style, she slept upright too many nights...she yawned.

Should she bathe? Soap was expensive. Water had to be lugged up two flights of stairs. She soaked in her shift, so how clean could she get? One rarely bathed. She should at least sprinkle rosemary over her body.

He'd swagger up the stairs any moment, sweaty from riding, clothes filthy, breath foul. She'd avoid kissing him.

**Researching my novel, The False Light, I found many interesting details about the eighteenth century. I like to write the gritty truth about life in another era, not the cleaned-up, idealized version.**

Diane Scott Lewis

Wednesday, June 30, 2010

Love in the Eighteenth Century?

I'm a former Navy Radioman (person) from California, married to a retired Navy chief. I've always loved to write and discover the past. I have two sons and two granddaughters.

I'm a former Navy Radioman (person) from California, married to a retired Navy chief. I've always loved to write and discover the past. I have two sons and two granddaughters.

Hostage Queen

I am a compulsive buyer of books, both new and second hand and one day was browsing along my shelves when I spotted one I’d bought years ago in Hay-on-Wye. It was called Queen of Hearts, written back in the 60s by Charlotte Haldane. It proved to be an autobiography of Marguerite de Valois and as I began to read I was immediately intrigued. Margot, as she was familiarly known, was no average woman, rather one born before her time, and I wanted to know more about her. So I began on a journey of twelve months research and discovery which led me to write a stirring tale of her adventures, her intrigues and passions, and the dangers she faced in the sixteenth century French Court.

Margot was the youngest of the three daughters of Henry II and Catherine de Medici. When our story begins in 1565, Catherine was a widow, her eldest son Francis II also dead. In addition, none of her three surviving sons enjoyed good health, so while in theory the crown of France was safe, there was no certainty that any of the Valois brothers would survive into old age, and these were risky times.

Margot had long been in love with Henri de Guise, but as with all royal princesses, was expected to bring political benefit through marriage. Various unlikely suitors were considered and rejected.

Here is the Duke of Guise, can you blame her for loving him?

In the end the Queen Mother, who had never showed much affection for this rebellious daughter, decided Margot should marry Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot, in order to bring to an end years of religious wars.

Margot wasn’t exactly thrilled by the prospect. Navarre was a third cousin whom she’d known from an early age, and she considered him something of a country bumpkin with garlic-tainted breath and grubby feet from climbing mountains barefoot.

There was also some resistance from his own mother, Jeanne d'Albret, but after she died, in somewhat suspicious circumstances, the wedding went ahead.

Navarre was a likeable enough fellow but not the faithful sort. Once Margot realised this, she thought what was sauce for goose… She embarked upon a string of love affairs, not least with Guise, a dangerous undertaking, and intrigue and scandal surrounded her at every turn. Both her brothers, first the half mad Charles IX, and then the bi-sexual Henri Trois with his mignons, pet dogs and monkeys, made furious attempts to control her, though with very little success. Henri frequently accused his sister of licentious behaviour, despite being far more guilty of that charge himself. He behaved like a rejected lover, jealous of the least attention she paid to any other man. He was even jealous of her love for their younger brother, Alençon, accusing the pair of plotting against him. He kept her a virtual prisoner in the Louvre for four years, and throughout that time Margot lived in fear of her life while recklessly flouting convention as far as she dare. Somehow she had to save her husband's life, help him to escape, and then follow him to safety. A task fraught with danger…

Margot was the youngest of the three daughters of Henry II and Catherine de Medici. When our story begins in 1565, Catherine was a widow, her eldest son Francis II also dead. In addition, none of her three surviving sons enjoyed good health, so while in theory the crown of France was safe, there was no certainty that any of the Valois brothers would survive into old age, and these were risky times.

Margot had long been in love with Henri de Guise, but as with all royal princesses, was expected to bring political benefit through marriage. Various unlikely suitors were considered and rejected.

Here is the Duke of Guise, can you blame her for loving him?

In the end the Queen Mother, who had never showed much affection for this rebellious daughter, decided Margot should marry Henry of Navarre, a Huguenot, in order to bring to an end years of religious wars.

Margot wasn’t exactly thrilled by the prospect. Navarre was a third cousin whom she’d known from an early age, and she considered him something of a country bumpkin with garlic-tainted breath and grubby feet from climbing mountains barefoot.

There was also some resistance from his own mother, Jeanne d'Albret, but after she died, in somewhat suspicious circumstances, the wedding went ahead.

Navarre was a likeable enough fellow but not the faithful sort. Once Margot realised this, she thought what was sauce for goose… She embarked upon a string of love affairs, not least with Guise, a dangerous undertaking, and intrigue and scandal surrounded her at every turn. Both her brothers, first the half mad Charles IX, and then the bi-sexual Henri Trois with his mignons, pet dogs and monkeys, made furious attempts to control her, though with very little success. Henri frequently accused his sister of licentious behaviour, despite being far more guilty of that charge himself. He behaved like a rejected lover, jealous of the least attention she paid to any other man. He was even jealous of her love for their younger brother, Alençon, accusing the pair of plotting against him. He kept her a virtual prisoner in the Louvre for four years, and throughout that time Margot lived in fear of her life while recklessly flouting convention as far as she dare. Somehow she had to save her husband's life, help him to escape, and then follow him to safety. A task fraught with danger…

Tuesday, June 29, 2010

How Many Historical Novelists Does It Take to Change a Light Bulb?

(From my individual blog)

How many historical novelists does it take to change a light bulb? A shocking 21, it turns out:

One to screw in the light bulb.

One to complain that the new light bulb is too dim for reading.

One to complain that the new light bulb is too bright for reading.

One to say that it's just right.

One to ask about how homes were illuminated in the (say) fourteenth century.

One to supply a list of references.

One to say that the list of references supplied is all wrong, and that he or she has better references.

One to say that it really doesn't matter, that readers only want a good story.

One to say that on the contrary, readers care deeply about how a house is illuminated and will be furious if the author gets it wrong.

One to suggest that the writer avoid the whole question by having all of his scenes take place in broad daylight.

One to mention that her new novel is getting great reviews.

One to point out that the new novel has nothing to do with the lighting question.

One to say that authors should support each other and that it should make no difference whether the new novel is relevant to the lighting question at all.

One to see whether Amazon has any books on the history of lighting and, while she's there, to check her Amazon rankings.

One to say that with e-readers, you really don't need to worry about light bulbs.

One to say that the printed book industry will never die and that e-books are just a passing fad.

One to try to make peace between everyone.

One to write about all of this on her blog.

One to send a Tweet about the blog post.

One to do a Facebook post about the light bulb issue.

One to call her agent to complain about the unproductive morning she has had reading all of the postings about light bulbs.

How many historical novelists does it take to change a light bulb? A shocking 21, it turns out:

One to screw in the light bulb.

One to complain that the new light bulb is too dim for reading.

One to complain that the new light bulb is too bright for reading.

One to say that it's just right.

One to ask about how homes were illuminated in the (say) fourteenth century.

One to supply a list of references.

One to say that the list of references supplied is all wrong, and that he or she has better references.

One to say that it really doesn't matter, that readers only want a good story.

One to say that on the contrary, readers care deeply about how a house is illuminated and will be furious if the author gets it wrong.

One to suggest that the writer avoid the whole question by having all of his scenes take place in broad daylight.

One to mention that her new novel is getting great reviews.

One to point out that the new novel has nothing to do with the lighting question.

One to say that authors should support each other and that it should make no difference whether the new novel is relevant to the lighting question at all.

One to see whether Amazon has any books on the history of lighting and, while she's there, to check her Amazon rankings.

One to say that with e-readers, you really don't need to worry about light bulbs.

One to say that the printed book industry will never die and that e-books are just a passing fad.

One to try to make peace between everyone.

One to write about all of this on her blog.

One to send a Tweet about the blog post.

One to do a Facebook post about the light bulb issue.

One to call her agent to complain about the unproductive morning she has had reading all of the postings about light bulbs.

I've published two historical novels set in fourteenth-century England and featuring the Despenser family: The Traitor's Wife: A Novel of the Reign of Edward II and Hugh and Bess. My third novel, The Stolen Crown, set during the Wars of the Roses, is narrated by Henry, Duke of Buckingham, and his wife, Katherine Woodville. My fourth novel, The Queen of Last Hopes focuses on Margaret of Anjou, one of the most maligned queens in English history. I am currently working on a novel set in Tudor England. I use this blog to post about history (mostly late medieval and Tudor England), historical fiction, and whatever strikes my fancy from time to time. Thanks for stopping by!

The title of this blog, by the way, comes from the song "Evil Woman" by the Electric Light Orchestra. Back when this song was new, I misheard the lyrics as "Medieval Woman."

Monday, June 28, 2010

BBC Historical Dramas

I have to admit I do have a passion for historical dramas and the BBC do it better than anyone!

Three that I thought I would mention here because I enjoyed them so much are:

First is Lark Rise To Candleford (There is currently 3 series).

Set in the aftermath of the first World War, Lillies is a quality period drama that centres on the activities of the Moss family. It’s also, seemingly, a show that’s been brought to an end after just one compelling series.

Set in the aftermath of the first World War, Lillies is a quality period drama that centres on the activities of the Moss family. It’s also, seemingly, a show that’s been brought to an end after just one compelling series.

Three that I thought I would mention here because I enjoyed them so much are:

First is Lark Rise To Candleford (There is currently 3 series).

Flora Thompson's charming love letter to a vanished corner of rural England is brought to life in this warm-hearted adaptation. Set in the Oxfordshire countryside in the 1880s, this rich, funny and emotive BBC series follows the relationship of two contrasting communities: Lark Rise, the small hamlet gently holding on to the past, and Candleford, the small market town bustling into the future.

Seen through the eyes of young Laura (Olivia Hallinan) the inhabitants endure many upheavals and struggles as the change inexorably comes; their stories by turns poignant, spirited and uplifting. And Laura herself must face great change. Taking a job in the Post Office in Candleford, run by the mercurial Dorcas Lane (Julia Sawalha - Cranford), Laura turns her back on her childhood hamlet to make her way in the world. With her loyalties divided, she must choose her own path to womanhood...

Dawn French, Julia Sawalha and Liz Smith star alongside Olivia Hallinan in this ten-part adaptation of Flora Thompson's magical memoir of her Oxfordshire childhood.

The second is, Cranford.

The cast boasts some of Britain's best-loved and most experienced actresses, including Dame Judi Dench, Dame Eileen Atkins, Imelda Staunton and Francesca Annis.

The five-part drama series tells the witty and poignant story of the small absurdities and major tragedies in the lives of the people of Cranford, as they are besieged by forces that they can't withstand.

Cranford in the 1840s is a small northern English town on the cusp of change. Things are on the move. The railway is pushing its way relentlessly towards the town from Manchester, bringing fears of migrant workers and the breakdown of law and order.

The arrival of handsome new doctor, Frank Harrison (Simon Woods) from London causes a stir; not only because of his revolutionary medical methods, but also because of the effect he has on many of the ladies' hearts in the town.

Judi Dench plays Miss Matty Jenkyns, whose hopes and rebellious spirit are crushed when she was forced as a young woman to give up Mr Holbrook (Michael Gambon), the man she loved.

Philip Glenister, Lesley Manville, Julia McKenzie, Julia Sawalha and Greg Wise also star alongside Judi Dench and the above-mentioned actors. Created by Sue Birtwistle and Susie Conklin for BBC One and written by Heidi Thomas (I Capture The Castle, Madam Bovary, Lilies).

The third is Lilies.

Set in the aftermath of the first World War, Lillies is a quality period drama that centres on the activities of the Moss family. It’s also, seemingly, a show that’s been brought to an end after just one compelling series.

Set in the aftermath of the first World War, Lillies is a quality period drama that centres on the activities of the Moss family. It’s also, seemingly, a show that’s been brought to an end after just one compelling series.Living in 1920s Liverpool, the Moss family consists of three girls--Iris, May and Ruby--and one boy, Billy. Trying to keep them in order is their father, following the death of their mother. The three girls, at the behest of their mother, are Catholics, and it’s they that Lillies concentrates the best of its time upon.

Other historical dramas recently bought and enjoyed:

Middlemarch

Miss Austen Regrets

Wives and Daughters

These dvds now join the exhaulted ranks of my favourites period dramas such as North And South (Elizabeth Gaskill), Pride & Prejudice, Becoming Jane, Sense & Sensibilty, Bleak House, North & South (USA civil war), Miss Potter, Rob Roy, Braveheart, The Patriot, Little Women and all the others that are on my shelves.

Saturday, June 26, 2010

History can be a matter of perspective

I recently hosted a chat on Coffee Time Romance, and one of the threads was about how to use a character’s POV, pet peeves and every day activities to add historical depth to manuscripts without using descriptive passages that stop the story.

We historical authors walk a tight rope. Too much historical detail and we bore our readers. Too little, and the period becomes nothing more than wallpaper—nice to look at but useless for adding depth to the story. One technique I use to create a three-dimensional historical world without drowning readers in minutia is to show characters doing something—or wanting something—that is not only in character, but also compares and contrasts to our world.

I have a good academic grounding in the medieval world, and a good sense of everyday life in the 12th century. But the fact is, I’ve never been there. I’ve never lived in a one-room croft with five other people, several geese and a cow. I’ve never gone weeks without a bath, and even though I grew up on a farm, I’ve never been responsible for growing, grinding and baking my own bread.

So to get a better sense of their world, I always invite my characters into my home. What they notice (or don’t) gives me a better understanding of how they interact with their world. Do they find the changes between the 12th century and now exciting or frightening? Do they admire our ingenuity or abhor our lack of community? Do the convenience of packaged food and a microwave outweigh the tastelessness of our meals?

Once I know what they love/hate about my world, I know which historical details I can use to anchor the story in time and place and which ones I can ignore. For instance, if they are willing to put up with microwave meals despite the lack of taste, then showing their frustration at the laborious process of food preparation could be a good way to show character and historical detail.

Tess, the heroine of my current book, TIES THAT BIND, was fascinated by three things from my world: Running water, central heating and the fact that I had so much space to myself.

Being able to turn a faucet and fill a sink—or even better, throw clothes in a metal drum and have them come out clean—literally blew her mind. In her wildest dreams, she never considered such things, and she’s used to hanging with Druids.

She also walked around my apartment wearing only a chemise while a snowstorm raged outside, and then marveled at the idea that if she didn’t want to see or talk to someone, she didn’t have to. Of course, I didn't take her to the local Jewel-Osco. Trips to the supermarket always end badly.

In the end, I didn’t include details on toting water or doing laundry because those activities weren’t relevant to the story. I did use Tess’ desire to be alone with her thoughts (something we’ve all wanted at some point) and the impossibility of finding that in a castle on a cold day in March. This allowed me to show a slice of everyday life and frustration for at least one person without ever saying castles were crowded places and privacy a foreign concept.

What techniques do you use to bring history alive in your book? Or if you’re a reader, can you think of an author or a book in which it’s done very well?

Labels:

historicals,

Keena Kincaid,

Ties That Bind

is a public relations consultant by day and a romance writer by night. In addition to being sleep deprived, she has four published books--Art of Love, and her historical paranormal trilogy, Druids of Duncarnoch: Anam Cara, Ties That Bind and Enthralled.

is a public relations consultant by day and a romance writer by night. In addition to being sleep deprived, she has four published books--Art of Love, and her historical paranormal trilogy, Druids of Duncarnoch: Anam Cara, Ties That Bind and Enthralled.

Tuesday, June 22, 2010

Let's hear it for Anne

In reading Tudor novels in the last year or two I've found it possible to pick up the idea that Anne Boleyn was considered less than aristocratic. Not that any author states such words in plain black and white; it is more the way in which authors describe her, have her contemporaries regard her, and select quotes that strengthen certain characteristics.

In reading Tudor novels in the last year or two I've found it possible to pick up the idea that Anne Boleyn was considered less than aristocratic. Not that any author states such words in plain black and white; it is more the way in which authors describe her, have her contemporaries regard her, and select quotes that strengthen certain characteristics.Yet she was born in Norfolk, most likely at Blickling Hall fifteen miles north of Norwich. Experts argue over a birth date of 1501 or 1507. Personally I go with 1507 because if she was in her mid to late twenties when Henry “noticed” her, there must have been a very good reason why she was not already married. And at such an advanced age, with no children as proof of fertility, she would not have been considered good breeding stock. Her father, Thomas, was eldest son to Sir William Boleyn of Blickling, and her mother, Elizabeth, was the daughter of Thomas Howard, Earl of Surrey and later Duke of Norfolk.

Seven of Anne’s great grandparents included a duke, an earl, the granddaughter of an earl, the daughter of one baron, the daughter of another and an esquire and his wife. She was better born than Henry’s three other English wives.

The only grandparent not of the nobility was Geoffrey Boleyn. He left Norfolk in the 1420s, made money as a London mercer and built Hever as a comfortable, moated manor house. He became lord mayor in 1457-8 and secured the daughter of Lord Hoo as his second wife. The oldest son of that marriage, William, was a leading Norfolk gentleman, knighted in 1483 and a JP who married the co-heiress of the wealthy Anglo-Irish Earl of Ormond.

While William was alive, he caused problems for his son, Thomas, Anne’s father. Though he would eventually inherit great wealth – the Boleyn and Hoo estates, half the Ormond fortune and half the lands of the wealthy Hankford family inherited from his Butler grandmother – Thomas had to live at Hever on £50 a year plus whatever his wife brought him, which wouldn’t be much, since her father had only just bought back the Howard lands he lost when he supported Richard III at Bosworth.

Thomas was not exactly penniless, but didn’t have enough money to do or live as he wished, so he entered service to the king. He attended Arthur’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon and escorted Margaret Tudor to Scotland for her marriage to King James, and by Henry VII’s death in 1509 had risen to the important rank of squire of the body. His father William died in 1505 and the old earl of Ormond was in his eighties, so Thomas had high expectations of wealth coming his way very soon. The Tudor court was at the sharp end of politics, where the important decisions were made, and his star was rising.

Thomas was not exactly penniless, but didn’t have enough money to do or live as he wished, so he entered service to the king. He attended Arthur’s marriage to Katherine of Aragon and escorted Margaret Tudor to Scotland for her marriage to King James, and by Henry VII’s death in 1509 had risen to the important rank of squire of the body. His father William died in 1505 and the old earl of Ormond was in his eighties, so Thomas had high expectations of wealth coming his way very soon. The Tudor court was at the sharp end of politics, where the important decisions were made, and his star was rising.In 1513 his daughter Anne went to the Hapsburg court at Mechelen in Brabant where she impressed with her cheerful demeanour and intelligence in spite of her young age. Today it is a town of some size between Antwerp and Brussels, but in Anne’s day it was a haven of aristocratic and princely behaviour where she served as maid of honour to Margaret of Austria. She would stay abroad for nine years, soon became bi-lingual and spent time in France as companion and lady in waiting at the French court. When she came home, of course she stood out among the provincial girls from the shires.

Labels:

Anne Boleyn,

Blickling Hall,

Thomas Boleyn

Sign up for my newsletter and receive a free eBook (PDF) in return. You'll find info and news, and special offers. Please sign up - I love to hear from readers and authors!

Sign up for my newsletter and receive a free eBook (PDF) in return. You'll find info and news, and special offers. Please sign up - I love to hear from readers and authors!

Monday, June 21, 2010

Victoria, Princess of Kent

By: Stephanie Burkhart

173 years ago on 20 June 1837, 18-year-old Princess Victoria of Kent succeeded to the throne. As Queen Victoria, she was one of Britain’s most endearing monarchs; as Princess Victoria of Kent and heir presumptive to the throne, her early life forged the strength and endurance she would display as a monarch.

Victoria’s story starts with the sad death of Charlotte Wales, the only legitimate child of George, Prince of Wales and Prince Regent at the time. In 1817, Charlotte, the heir to the throne was 20 years old. Her death was a tragedy. She died after giving birth to a stillborn son. The next generation, and England’s promising monarch, was gone.

At the time of Charlotte’s death, George III was king, but was a raving lunatic. His son, George, had been the Prince Regent since 1810. George, the Prince Regent was 55 years old when Charlotte died. He was estranged from his wife, and would have no more children.

His brothers, Fredrick, William, and Edward were middle-aged and unmarried, however they were devoted to their mistresses and lovers. It was time for them to seek out legitimate wives.

Edward, Duke of Kent, Victoria's Father

Fredrick was married, but estranged from his wife. He wasn’t having any legitimate children. (It was rumored he sired numerous bastards) William, Duke of Clarence, had a 20 year relationship with an actress, Dorothy Jordan, and they had 10 children. (illegitimate, of course) However, when Charlotte Wales died, William sought out a proper wife and married Adelaide of Saxe-Menigenen. Sadly, the two daughters William fathered with Adelaide died in infancy.

Victoria’s father, Edward, was chosen to approach Victoria, a German princess of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield. (to be referred to as Victoria of SCS to differentiate her from her daughter, Victoria.) Victoria was older, 31, a widow with two young sons.

At the time, Edward had lived with his lover, Madame St. Laurent. She was not British royalty, and had in fact, escaped from the French Revolution. According to the Royal Marriages Act, he was not allowed to marry her. Knowing he now had a duty to take a legitimate wife, Edward set out to Germany to propose to Victoria of SCS.

There’s an interesting little side note which Jean Plaidy, (Victoria Holt writing with a pen name) wrote about in her book, “Victoria Victorious,” that relates how Edward, on his way to visit his future wife in Germany stopped to stay the night at an inn. A gypsy was there, and for a lark, he asked her to tell him his fortune. She said he would father a great Queen. He insisted that it be a king, but the gypsy said no, he would father a queen. Moved by these words, Edward carried out his plans to marry Victoria of SCS with no regrets.

Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfield, Victoria's Mother

In May 1819, Young Victoria of Kent was born at Kensington Palace.

The Prince Regent didn’t care for Victoria’s mother. It’s hard to say at this point why. (Later, it would be Victoria of SCS employment of John Conroy which would fuel the dislike.) Plaidy implies that the Prince Regent thought Victoria of SCS had bad taste. He was a real dandy and everything he did was in good taste. The initial conflict stemmed from that.

When it came time for baby Victoria to be christened, etiquette demanded the Regent approve her names. Needless to say, George, Edward, and his wife didn’t agree.

Baby Victoria was presented to the Regent. George said, “Name her Alexandrina.” (After Alexander I of Russia, Britain’s ally in the Napoleonic wars) Edward winced. He whispered, “Charlotte” to George.

George shook his head in disapproval.

“Augusta,” suggested Edward.

“Name her Victoria after her mother,” said George. Then he walked off.

So instead of having a dynastic name, young Victoria was given only two names that weren’t in the House of Hanover.

Edward was poor. He’d gotten some money for his household, but not enough. He contemplated going to Germany to live because it was cheaper, but caught a cold which quickly turned into pneumonia. He died just 8 months after his daughter was born.

George III died in 1820 and the Prince Regent became George IV. Fredrick, his brother became the Heir Presumptive.

Victoria of SCS was to quarrel with George IV the rest of his life. After Edward’s death, Victoria of SCS hired John Conroy to help run her house. George IV (and later his brother, William IV) disapproved of him, seeing him for the money grubber he was. It was rumored John Conroy and Victoria of SCS were lovers.

As a child, Victoria learned to speak German first. After she turned 3, she was taught English. Young Victoria was subject to what her mother called the Kensington System. Someone had to be with Victoria at all times – even in the bedroom. They had to hold her hand going upstairs. Young Victoria never slept alone.

Victoria wrote in her diary often. As a young girl, she would visit George IV and call him Uncle King. George IV enjoyed the young girl’s company, but because of his dislike for Victoria of SCS, the visits to Uncle King weren’t as often as Young Victoria would have liked.

Victoria had a fair education, but led a very sheltered life because of her mother’s Kensington System. In 1827, Fredrick died, making William of Clarence the Heir Presumptive. George IV died in 1830, making William king. William was 65 years old when he became king. Young Victoria was now the Heir Presumptive.

Emily Blount as "Queen Victoria"

Victoria was 11 when Uncle King died. It was during this time she learned her importance to the throne. Her governess, Baroness Lehzen, showed her a book of the House of Hanover and Victoria’s place in it. When young Victoria realized her role in the succession, she was reported to have said, “I will be good.”

In 1830, Parliament passed the Regency Act, naming Victoria of SCS Regent should Victoria come to the throne before her 18th birthday.

William shuddered at the thought of a regency knowing how Victoria SCS and John Conroy were. He was determined to hang onto the crown until Victoria turned 18 and could take the throne without a regency. He did what he could to see Victoria, offering her a salary and her own house without her mother, but his attempts were rebuffed by Victoria of SCS.

Now a teenager, Victoria was determined to assert her independence. She could see how bad the restrictive polices of her mother and John Conroy were. Conroy tried time and again to get young Victoria to accept a regency, but she refused.

Emily Blount and Rupert Friend from the movie, Young Victoria

Stubborn William IV lived to see Victoria’s 18th birthday in May 1837. He died a month later on 20 June 1837.

Victoria was told of the king’s passing in the middle of the night. She expressed her sorrow, but issued her first edict – that night, for the first time in her life Victoria slept in her room alone.

Epilogue: When Victoria met with her privy council for the first time, the proclamation was drafted for “Alexandrina Victoria" to sign (her names, right?) She simply signed it, “Victoria.”

Labels:

Jean Plaidy,

Princess of Kent,

Young Queen Victoria

A member of Generation X, Stephanie was born in Manchester, New Hampshire. After graduating from Central High, she joined the U.S. Army. She spent 11 years in the military, 7 stationed in Germany. While in the military she earned her B.S. in Political Science from California Baptist University in Riverside, CA in 1995. She left the Army in 1997 and settled in California. She now works for LAPD as a 911 Dispatcher. The New England Patriots are still her favorite football team. Stephanie has been married for over 19 years. She has two boys, Andrew, 8, and Joseph, 4.

A member of Generation X, Stephanie was born in Manchester, New Hampshire. After graduating from Central High, she joined the U.S. Army. She spent 11 years in the military, 7 stationed in Germany. While in the military she earned her B.S. in Political Science from California Baptist University in Riverside, CA in 1995. She left the Army in 1997 and settled in California. She now works for LAPD as a 911 Dispatcher. The New England Patriots are still her favorite football team. Stephanie has been married for over 19 years. She has two boys, Andrew, 8, and Joseph, 4.

Sunday, June 20, 2010

The past is another country...

...They do things differently there.' (L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between)

...They do things differently there.' (L. P. Hartley, The Go-Between)Setting any story in the distant past brings its own delights and perils. For me it allows my heroines to be engaging and ingenious, sometimes accepting historical society's conventions and restrictions, sometimes going against them, but always provoking inner or outward conflict. Heroes can be shown off to great advantage, really doing something - protecting, rescuing, struggling with great war-horses, battling the elements or the bad guys.

However, the backdrop against which all this high-stakes, high-adventure romance takes place needs to be carefully drawn and considered. Fashions are different, right down to underwear (or lack of it). Transport, law, weapons, animals, trees, climate, customs - these can all be very different from the present.

My oldest book, in both creative genesis and the date at which it is set, is Bronze Lightning. This is set in the Bronze Age, before the eruption of Thera (the modern Greek island of Santorini), the island shown below in a Bronze age fresco. Some structures, such as the pyramids and Stonehenge, were already old when the story opens in 1562 BC, although these also looked different. The pyramids I have imagined with their wonderful limestone covering, which would have made them gleam a brilliant white in the landscape. Stonehenge was also complete and not yet fallen into the decay already familiar when Constable created his painting of it.

My oldest book, in both creative genesis and the date at which it is set, is Bronze Lightning. This is set in the Bronze Age, before the eruption of Thera (the modern Greek island of Santorini), the island shown below in a Bronze age fresco. Some structures, such as the pyramids and Stonehenge, were already old when the story opens in 1562 BC, although these also looked different. The pyramids I have imagined with their wonderful limestone covering, which would have made them gleam a brilliant white in the landscape. Stonehenge was also complete and not yet fallen into the decay already familiar when Constable created his painting of it.Ritual places are not the only things that were different in the distant past. Some activities, such as the smelting of metals, farming, brewing, the making of clothes, were all different from what came later and very different from our own time.

Beliefs and religion were also very different and, given the few written sources we have from Bronze Age Europe, must be inferred from archaeology and other means. Fearn the hero believes in a Sky God who has some characters that are similar to the later Viking God Thor: all later religions tend to have 'clues' of past faiths in them. He also undergoes a trance state where he sees symbols that modern shamans have also reported seeing in trances and which have been painted by cave painters.

Beliefs and religion were also very different and, given the few written sources we have from Bronze Age Europe, must be inferred from archaeology and other means. Fearn the hero believes in a Sky God who has some characters that are similar to the later Viking God Thor: all later religions tend to have 'clues' of past faiths in them. He also undergoes a trance state where he sees symbols that modern shamans have also reported seeing in trances and which have been painted by cave painters.In Bronze Lightning I bring the heroine Sarmatia right to my own doorstep. The winter house she lives in is set where my parents' house is now, and the wild apple and cherry trees she sees in blossom are ones I have known since childhood. Lots of other details are changed, however, because the distant past truly is another country.

In the Bronze Age, the climate in England was warmer and drier than today. There was much more woodland, and animals such as beavers, bears, wolves and wild boar in the woods. We have lost all these creatures excerpt for the boar, which has escaped from farms in southern England and is making its home in woodland again. Lime trees flourished, and orchids and other flowers that are rare or extinct today. The sheep Sarmatia care for were more like Soay sheep, that do not flock and whose fleece is not at all like the thick fleeces of modern breeds. The cattle were smaller or completely wild. Even the stars she followed were different. Even the polar star hung in a different place in the Bronze Age.

I exploit these differences to show the past in my story, to remind my readers that they are in another time, another place... where magic and romance do truly go hand in hand.

Thursday, June 10, 2010

A Medieval Love Story: Ralph de Monthermer and Joan of Acre

One of the more unlikely romances in the late thirteenth century was that between Joan of Acre, daughter of King Edward I, and Ralph de Monthermer, son of the Lord Knows Who. For Ralph, a squire in Joan's household, was of such obscure origins that his parentage is unknown.

Joan of Acre (whose daughter Eleanor de Clare is the heroine of my first novel, The Traitor's Wife) was born in 1272 in Acre, or Akko, in what is now Israel. Her parents, Eleanor of Castile and the future Edward I, had gone there on crusade. Joan was soon sent to her maternal grandmother in Castile, where she remained until 1278. Her father, now King of England, had plans to marry her to Hartman, son of the King of the Romans, but the young man died in a shipwreck in 1282 before the couple could marry. Undaunted, Edward I soon began searching around for another suitable husband. Soon he lit on one: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, probably the most powerful baron in England at the time and one whose relations with the king had long been stormy. Gilbert had the disadvantage of already having a wife, Alice de Lusignan, but the couple had long been estranged, and in 1285, the marriage was annulled. In 1290, after drawn-out negotiations and the obtaining of a papal dispensation, eighteen-year-old Joan was finally married to forty-six-year-old Gilbert. Before Gilbert's death in December 1295, the couple efficiently produced four children: Gilbert, Eleanor, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Joan has taken hard knocks at the hands of both historians and novelists. Mary Anne Everett Green in her Lives of the Princesses of England characterizes her as a neglectful mother and a "giddy princess," and other Victorian-era historians, along with many novelists, have acquiesced in this judgment. There seems to be little evidence to support the charges of neglect; though Edward I did arrange for Joan's son Gilbert to live at court when he was seven, this was hardly an atypical arrangement for a noble boy who was also the king's grandson, and children of this social class often were separated from their parents for long periods. As for Joan's giddiness, Michael Altschul has commented on the "marked ability" with which Joan controlled the Clare lands after Gilbert's death.

What can be said about Joan, however, was that she had spirit and willfulness. During her parents' absence in Gascony, when Joan was in her early teens, she became involved in a dispute with the treasurer of her household and refused to accept money from him; her father had to pay her debts when he returned to England. After her marriage, she left court to be alone with her new husband at his manors, to the displeasure of her father, who in reprisal seized seven robes that had been made for her.

Among the squires in Gilbert de Clare's vast household was one Ralph de Monthermer. Nothing is known of his background, but he soon caught the eye of his widowed mistress, who sent him to her father to be knighted. Sometime at the beginning of 1297, the couple were secretly married.

Edward I, cheerfully ignorant of this match, had meanwhile been searching around for another husband for his daughter, and it is safe to say that Monthermer was not on the king's shortlist. The king's words when he heard the rumors about his daughter's attraction to her squire are unrecorded, and in any case are probably best left to the imagination. He seized Joan's estates and formally announced his daughter's betrothal to the Count of Savoy in March 1297. Joan, however, had become "conscious that she was in a situation which would render the disclosure of her marriage inevitable," as Green delicately puts it, and she apparently broke the news of the marriage to her father, who promptly clapped Monthermer into prison at Bristol Castle.

Either before informing her father of her marriage or after Monthermer had been put into prison--the accounts vary--Joan sent her little daughters to visit their grandfather the king in hopes that they would soften his mood. Evidently, though, more was needed than just the youthful antics of the three Clare sisters. After a great deal of discussion at court about the matter, Joan, as the chronicles report, was at last allowed to plead for herself before her father, at which time she is said to have told the king that as it was no disgrace for an earl to marry a poor woman, it was not blameworthy for a countess to advance a capable young man. This defense is said to have pleased Edward I, though it is probable that Joan's pregnancy, which would have been visible at the time of this exchange in July 1297, also convinced the king to accept the situation. He restored most of Joan's lands to her and pardoned Monthermer, who from November 1297 onward was referred to as the Earl of Gloucester. In the meantime, the couple's first child, named Mary, had been born. She was followed by three others: Thomas, Edward, and Joan.

Ralph soon found himself busy fighting Scots for his new father-in-law, which brought him quickly into favor with the king. In 1301, Edward I restored Tonbridge and Portland to Ralph and Joan in consideration of Ralph's good services in Scotland. Ralph also was on cordial terms with young Prince Edward, who frequently wrote to him. Joan too was friendly with her much younger brother Edward, even offering him her seal when Edward was estranged from his father.

On April 23, 1307, Joan of Acre died. Some Internet sources claim that she died in childbirth--unfortunately, hardly an implausible scenario--but none that I have seen mention a source for this information. Neither Green, Altschul, nor Frances Underwood specify a cause for her death. She was only thirty-five. Ralph was probably not present, being engaged in Scotland at the time. Joan was buried at the priory of Clare in Suffolk. According to Underwood, Osbern Bokenham, a friar there, relayed the odd story that in 1359, Elizabeth de Burgh, Joan's last surviving Clare daughter, inspected her mother's body and found the corpse to be intact. Bokenham also reported that miracles were said to occur at Joan's tomb, including the healing of toothache, back pain, and fever.

Edward I, who ordered that masses be said for his daughter, was himself in poor health; he died in July 1307. Having been styled an earl in right of his wife, Ralph lost his title shortly after her death; Joan and Gilbert de Clare's son, another Gilbert, became the next Earl of Gloucester. The new king, Edward II, granted Ralph five thousand marks for his surrender of the Clare lands to Gilbert, then still a minor. Though his importance had been much diminished, Ralph remained active in Edward II's reign, holding positions such as keeper of the forest south of Trent, and seems to have been neutral or on the king's side during the latter's disputes with his barons. In 1314, he was taken prisoner at Bannockburn but was treated as an honored guest by Robert Bruce, who allowed him to return to England without having to pay a ransom. A story goes that years before, Monthermer, having gotten wind of a plan of Edward I to capture Bruce while he was in London, had sent him a pair of spurs and coins bearing the king's head as a hint that he should slip away. Bruce, having profited from the hint, later remembered this good deed when Monthermer became his prisoner.

Ralph died on April 5, 1325, and was buried in the Grey Friars' church at Salisbury. His descendants through Joan of Acre include Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, who helped bring Edward IV to the throne. Warwick's daughter Anne married the future Richard III. It was an impressive lineage for Ralph de Monthermer, the obscure squire who had married a princess.

Joan of Acre (whose daughter Eleanor de Clare is the heroine of my first novel, The Traitor's Wife) was born in 1272 in Acre, or Akko, in what is now Israel. Her parents, Eleanor of Castile and the future Edward I, had gone there on crusade. Joan was soon sent to her maternal grandmother in Castile, where she remained until 1278. Her father, now King of England, had plans to marry her to Hartman, son of the King of the Romans, but the young man died in a shipwreck in 1282 before the couple could marry. Undaunted, Edward I soon began searching around for another suitable husband. Soon he lit on one: Gilbert de Clare, Earl of Gloucester, probably the most powerful baron in England at the time and one whose relations with the king had long been stormy. Gilbert had the disadvantage of already having a wife, Alice de Lusignan, but the couple had long been estranged, and in 1285, the marriage was annulled. In 1290, after drawn-out negotiations and the obtaining of a papal dispensation, eighteen-year-old Joan was finally married to forty-six-year-old Gilbert. Before Gilbert's death in December 1295, the couple efficiently produced four children: Gilbert, Eleanor, Margaret, and Elizabeth.

Joan has taken hard knocks at the hands of both historians and novelists. Mary Anne Everett Green in her Lives of the Princesses of England characterizes her as a neglectful mother and a "giddy princess," and other Victorian-era historians, along with many novelists, have acquiesced in this judgment. There seems to be little evidence to support the charges of neglect; though Edward I did arrange for Joan's son Gilbert to live at court when he was seven, this was hardly an atypical arrangement for a noble boy who was also the king's grandson, and children of this social class often were separated from their parents for long periods. As for Joan's giddiness, Michael Altschul has commented on the "marked ability" with which Joan controlled the Clare lands after Gilbert's death.

What can be said about Joan, however, was that she had spirit and willfulness. During her parents' absence in Gascony, when Joan was in her early teens, she became involved in a dispute with the treasurer of her household and refused to accept money from him; her father had to pay her debts when he returned to England. After her marriage, she left court to be alone with her new husband at his manors, to the displeasure of her father, who in reprisal seized seven robes that had been made for her.

Among the squires in Gilbert de Clare's vast household was one Ralph de Monthermer. Nothing is known of his background, but he soon caught the eye of his widowed mistress, who sent him to her father to be knighted. Sometime at the beginning of 1297, the couple were secretly married.

Edward I, cheerfully ignorant of this match, had meanwhile been searching around for another husband for his daughter, and it is safe to say that Monthermer was not on the king's shortlist. The king's words when he heard the rumors about his daughter's attraction to her squire are unrecorded, and in any case are probably best left to the imagination. He seized Joan's estates and formally announced his daughter's betrothal to the Count of Savoy in March 1297. Joan, however, had become "conscious that she was in a situation which would render the disclosure of her marriage inevitable," as Green delicately puts it, and she apparently broke the news of the marriage to her father, who promptly clapped Monthermer into prison at Bristol Castle.

Either before informing her father of her marriage or after Monthermer had been put into prison--the accounts vary--Joan sent her little daughters to visit their grandfather the king in hopes that they would soften his mood. Evidently, though, more was needed than just the youthful antics of the three Clare sisters. After a great deal of discussion at court about the matter, Joan, as the chronicles report, was at last allowed to plead for herself before her father, at which time she is said to have told the king that as it was no disgrace for an earl to marry a poor woman, it was not blameworthy for a countess to advance a capable young man. This defense is said to have pleased Edward I, though it is probable that Joan's pregnancy, which would have been visible at the time of this exchange in July 1297, also convinced the king to accept the situation. He restored most of Joan's lands to her and pardoned Monthermer, who from November 1297 onward was referred to as the Earl of Gloucester. In the meantime, the couple's first child, named Mary, had been born. She was followed by three others: Thomas, Edward, and Joan.

Ralph soon found himself busy fighting Scots for his new father-in-law, which brought him quickly into favor with the king. In 1301, Edward I restored Tonbridge and Portland to Ralph and Joan in consideration of Ralph's good services in Scotland. Ralph also was on cordial terms with young Prince Edward, who frequently wrote to him. Joan too was friendly with her much younger brother Edward, even offering him her seal when Edward was estranged from his father.

On April 23, 1307, Joan of Acre died. Some Internet sources claim that she died in childbirth--unfortunately, hardly an implausible scenario--but none that I have seen mention a source for this information. Neither Green, Altschul, nor Frances Underwood specify a cause for her death. She was only thirty-five. Ralph was probably not present, being engaged in Scotland at the time. Joan was buried at the priory of Clare in Suffolk. According to Underwood, Osbern Bokenham, a friar there, relayed the odd story that in 1359, Elizabeth de Burgh, Joan's last surviving Clare daughter, inspected her mother's body and found the corpse to be intact. Bokenham also reported that miracles were said to occur at Joan's tomb, including the healing of toothache, back pain, and fever.

Edward I, who ordered that masses be said for his daughter, was himself in poor health; he died in July 1307. Having been styled an earl in right of his wife, Ralph lost his title shortly after her death; Joan and Gilbert de Clare's son, another Gilbert, became the next Earl of Gloucester. The new king, Edward II, granted Ralph five thousand marks for his surrender of the Clare lands to Gilbert, then still a minor. Though his importance had been much diminished, Ralph remained active in Edward II's reign, holding positions such as keeper of the forest south of Trent, and seems to have been neutral or on the king's side during the latter's disputes with his barons. In 1314, he was taken prisoner at Bannockburn but was treated as an honored guest by Robert Bruce, who allowed him to return to England without having to pay a ransom. A story goes that years before, Monthermer, having gotten wind of a plan of Edward I to capture Bruce while he was in London, had sent him a pair of spurs and coins bearing the king's head as a hint that he should slip away. Bruce, having profited from the hint, later remembered this good deed when Monthermer became his prisoner.

Ralph died on April 5, 1325, and was buried in the Grey Friars' church at Salisbury. His descendants through Joan of Acre include Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, who helped bring Edward IV to the throne. Warwick's daughter Anne married the future Richard III. It was an impressive lineage for Ralph de Monthermer, the obscure squire who had married a princess.

I've published two historical novels set in fourteenth-century England and featuring the Despenser family: The Traitor's Wife: A Novel of the Reign of Edward II and Hugh and Bess. My third novel, The Stolen Crown, set during the Wars of the Roses, is narrated by Henry, Duke of Buckingham, and his wife, Katherine Woodville. My fourth novel, The Queen of Last Hopes focuses on Margaret of Anjou, one of the most maligned queens in English history. I am currently working on a novel set in Tudor England. I use this blog to post about history (mostly late medieval and Tudor England), historical fiction, and whatever strikes my fancy from time to time. Thanks for stopping by!

The title of this blog, by the way, comes from the song "Evil Woman" by the Electric Light Orchestra. Back when this song was new, I misheard the lyrics as "Medieval Woman."

Tuesday, June 8, 2010

Violent Lives

The Stewart kings are hard to beat for having lived life on the edge. Consider, if you will, this deliberately truncated history:

In 1406 Robert III of Scotland sent his twelve-year-old son James to France for safety. The boy was captured at sea by the English. Robert died on hearing the news and James I remained in captivity until 1424. He married Joan Beaufort, daughter of the first earl of Somerset and niece of King Henry IV of England. In February 1437 he was undressing for bed when eight assassins, led by Sir Robert Graham, burst into the King’s chamber in Perth and stabbed him to death.

His son, James II was six years old at the time. The Stewart and Douglas factions carried on a merry civil war until James came of age in 1449 and married Mary of Gueldres, thus reinforcing Scotland’s connection with France. He stabbed the eighth earl of Douglas to death at Stirling Castle in February 1452 because Douglas ‘resisted the King’s gentle persuasions.’ In 1453 and again in 1455 James pillaged Douglas lands. Whilst at Roxburgh expelling the English garrison, an exploding cannon killed him. He was twenty-nine years old.

His son James III was then nine years old. He assumed power in 1469 and married Anne of Denmark, who brought Orkney and Shetland as her dowry. He imprisoned his brothers Albany and Mar to protect his throne from plotters. Albany escaped to France, intrigued with the Earl of Douglas and formed an alliance with Edward IV of England, promising to be his vassal if Edward could secure the Scottish throne for him. In 1482 Albany invaded Scotland as Alexander IV with an English army led by Richard of Gloucester, later Richard III. James was imprisoned and in 1488 was forced to fight his son at the battle of Sauchieburn. James, defeated, escaped but was discovered and murdered, callously stabbed by a passer-by who claimed to be a priest.

James IV was then fifteen. He married Margaret Tudor, elder sister of Henry VIII, and relations with his brother-in-law deteriorated over Henry’s refusal to hand over Margaret’s dowry. It was one of the vexations that led to the battle of Flodden in 1513, where James died, along with 13 earls, 14 lords, an archbishop, a bishop, two abbots and numerous knights.

James V was a mere infant in 1513, and Scotland endured the misery of a long minority. He broke free of the Regent, the Earl of Angus, in 1528 and seized power himself. When he invaded England in 1542, his army was routed at Solway Moss. James is said to have visited his mistress at Tantallon, then his very pregnant wife Mary of Guise at Edinburgh, and retreated to Falkland in Fife where before he died he commented bleakly ‘it came wi a lass, and it’ll gang with a lass.’ Some think this referred to the Maid of Norway, the sole surviving heir in 1290, and some think it referred to Marjorie Bruce in 1315.

Either way, the lass born in 1542 grew up to be Mary Queen of Scots. She was beheaded by Elizabeth in 1587, leaving one son, James, to inherit both the Scottish and English thrones.

It is interesting to reflect that James I and VI had a mother who all her life was considered essentially French; a French grandmother, an English great-grandmother, a Danish gt gt grandmother and a Burgundian gt gt gt grandmother. On the male side, his father was raised in England, his grandfather was half English, quarter Scot, quarter Danish; his gt grandfather was a mixture of Danish, Burgundian, Scottish and English.

Labels:

Scottish history,

Stewart Kings

Sign up for my newsletter and receive a free eBook (PDF) in return. You'll find info and news, and special offers. Please sign up - I love to hear from readers and authors!

Sign up for my newsletter and receive a free eBook (PDF) in return. You'll find info and news, and special offers. Please sign up - I love to hear from readers and authors!

Monday, June 7, 2010

Time Travel and Historical Research

When I was first invited to join this oustanding group of writers I was, in a word, thrilled. I've been a devoted fan of historial fiction and romance since my teens and my thirst for the genre has never dimmed. I have one series, at the moment, that is historical, my western Bride series. It often seems to me westerns, even western romance, is very much its own genre, but it is still historical.

Mostly I write time travels. Most of the time you see time travels listed as fantasy or perhaps science fiction. But they cross over into historical (or futuristic) either when the hero or heroine comes to the present or they travel back in time. I think time travels offer readers and authors a rich opportunity to explore the realm of "what if."

I had one of those "what if" moments while working on my last WIP this past week. I knew where I wanted to go with my antagonist, but I just wasn't getting there. I'd spent hours looking through medieval punishments, things we'd consider torture today and, in fact, they refer to it as torture on the websites. They had some mighty creative ways of punishing wrong doers back then. It's amazing what the human mind can come up with.

Among my favorites were the Brank where the The Brank was used to humiliate women who got involved in brawling with her neighbours or generally breaking the peace, or just being a public nuisance to the neighbourhood, women who gossiped with no purpose other than to offend, ridicule or lie about someone else were subject to this torture.

The device was a metal cage or mask that enclosed the head, often with ridiculous adornments designed to humiliate its victim. In some towns, the Brank had a bell attached to its rear only to announce the presence of the victim who was instantly mocked by the people she "endangered" through gossip.

The other was the Street Sweeper's Daughter which while it may have been used in Englaish, was mostly found in in Russia and the Middle East.

The Street Sweeper's Daughter worked by compressing the victim's body; just like The Rack, but inversely so. The torturer Could tighten the device or loosen it up, depending on the victim's offense.

This device although not very painful-looking, was often employed publicly to humiliate the victim. Those particularly hated individuals were often at the mercy of an angry crowd that often threw stones and fecal maters to the exposed victim. The immobilized victim was also frequently led to madness, as the torture period could last for weeks or months.

As to what this has to do with romance? Well, if someone was making your life difficult at best, wouldn't you love to have your hero give him, or her, a bit of a comeuppance? Justice can be grand.

I found, however, that while reading through these different devices was interesting, they weren't doing much to move my story along. Where did my villian go from there? I stumbled on a much more creative avenue, one that will lead to book 3 of the series. One that gives my heroine a much more romantic ending. While a year out before it is published, the possibilities are limitless.

Mostly I write time travels. Most of the time you see time travels listed as fantasy or perhaps science fiction. But they cross over into historical (or futuristic) either when the hero or heroine comes to the present or they travel back in time. I think time travels offer readers and authors a rich opportunity to explore the realm of "what if."

I had one of those "what if" moments while working on my last WIP this past week. I knew where I wanted to go with my antagonist, but I just wasn't getting there. I'd spent hours looking through medieval punishments, things we'd consider torture today and, in fact, they refer to it as torture on the websites. They had some mighty creative ways of punishing wrong doers back then. It's amazing what the human mind can come up with.

Among my favorites were the Brank where the The Brank was used to humiliate women who got involved in brawling with her neighbours or generally breaking the peace, or just being a public nuisance to the neighbourhood, women who gossiped with no purpose other than to offend, ridicule or lie about someone else were subject to this torture.

The device was a metal cage or mask that enclosed the head, often with ridiculous adornments designed to humiliate its victim. In some towns, the Brank had a bell attached to its rear only to announce the presence of the victim who was instantly mocked by the people she "endangered" through gossip.

The other was the Street Sweeper's Daughter which while it may have been used in Englaish, was mostly found in in Russia and the Middle East.

The Street Sweeper's Daughter worked by compressing the victim's body; just like The Rack, but inversely so. The torturer Could tighten the device or loosen it up, depending on the victim's offense.

This device although not very painful-looking, was often employed publicly to humiliate the victim. Those particularly hated individuals were often at the mercy of an angry crowd that often threw stones and fecal maters to the exposed victim. The immobilized victim was also frequently led to madness, as the torture period could last for weeks or months.

As to what this has to do with romance? Well, if someone was making your life difficult at best, wouldn't you love to have your hero give him, or her, a bit of a comeuppance? Justice can be grand.

I found, however, that while reading through these different devices was interesting, they weren't doing much to move my story along. Where did my villian go from there? I stumbled on a much more creative avenue, one that will lead to book 3 of the series. One that gives my heroine a much more romantic ending. While a year out before it is published, the possibilities are limitless.

Labels:

medieval prisons,

Regan Taylor,

time travel

I am Miss Missy, Empress of the Universe, Daughter of Satan, but you can call me Your Majesty.

Saturday, June 5, 2010

Fact or Fiction? The French Revolution

Donating jewelry for the cause.

While researching the French Revolution for my historical romance, Hostage to Fortune, I discovered something interesting that you may have come across. It might be more myth than fact, but nevertheless fascinating. In 1793, the Dauphin Louis-Charles became king in the eyes of the Royalists. After he was locked up in the Tower, did he survive? Lady Atkyns, a Drury Lane actress and a close friend of Marie Antoinette tried first to rescue the queen, but when that lady refused to leave her children, she made a promise to save the dauphin, which she tried desperately to keep. Her attempt to abduct Louis-Charles from the Tower seems to have failed. But there is speculation that a mute boy was substitued for the young king, after he was removed and either murdered or allowed to live in obsurity with a peasant family. The mute boy was then held for the ten years he lived, hidden from the world. In 1821 a man appeared in London declaring he was the dauphin. This claim was summarily dismissed. In fact, there were forty candidates who came forward to declare themselves Louis-Charles, under the Restoration. The most important of these pretenders were Karl Wilhelm Naundorff and the comte de Richemont. Naundorff's story rested on a series of complicated intrigues. According to him Barras determined to save the dauphin in order to please Josephine Beauharnais, the future empress, having conceived the idea of using the dauphin's existence as a means of dominating the comte de Provence in the event of a restoration. In this version, the dauphin was concealed in the fourth storey of the Tower, a wooden figure being substituted for him. Great fodder for a novel, and of course, I've used it.

For those interested, here's a link: http://www.1911encyclopedia.org/Louis_XVII

I write sensual historical romance where heroes meet their match in feisty heroines. Add a dash of adventure, a murder or two, a mystery or intrigue. What better time to set them than the Georgian, Regency and the late Victorian period on the brink of the 20th Century.

The Regency was a time of both opulence and abject poverty. Of economic and social change: the Napoleonic wars, the power struggle for the Americas, and the Industrial revolution when people began to desert the country for the cities.

Celebrity Lord Byron wrote dark romantic poetry, and Beau Brummell defined and shaped fashion into a period of simplistic elegance. Men abandoned brocades and lace for linen trousers, overcoats with breeches and boots, and women abandoned corsets for high wasted, thin gauzy dresses.

A spend-thrift aesthete known for his scandalous affairs, George IV, the Prince of Wales was made Regent in 1811 after his father was declared too mad to rein. Prinny presided over the elegant society of the ton, the Upper Ten Thousand, who defined themselves by an incredibly formal etiquette code which set them apart from the rising middle class.

I write sensual historical romance where heroes meet their match in feisty heroines. Add a dash of adventure, a murder or two, a mystery or intrigue. What better time to set them than the Georgian, Regency and the late Victorian period on the brink of the 20th Century.

The Regency was a time of both opulence and abject poverty. Of economic and social change: the Napoleonic wars, the power struggle for the Americas, and the Industrial revolution when people began to desert the country for the cities.

Celebrity Lord Byron wrote dark romantic poetry, and Beau Brummell defined and shaped fashion into a period of simplistic elegance. Men abandoned brocades and lace for linen trousers, overcoats with breeches and boots, and women abandoned corsets for high wasted, thin gauzy dresses.

A spend-thrift aesthete known for his scandalous affairs, George IV, the Prince of Wales was made Regent in 1811 after his father was declared too mad to rein. Prinny presided over the elegant society of the ton, the Upper Ten Thousand, who defined themselves by an incredibly formal etiquette code which set them apart from the rising middle class.

Friday, June 4, 2010

Queen for a Day

Today, the 4th of June, is the official launch of my debut novel, so I feel entitled to be Queen of my own backyard just for today, and to celebrate the achievement with champagne and cake! ( And I hope you had a good celebration too Lindsay, for your publication day.)

But on this date, the 4th of June, 474 years ago Jane Seymour was enthroned Queen of England after a whirlwind engagement and speedy marriage to Henry VIII. Ann Boleyn was beheaded on the 19th May, and Henry wasted no time - he set off straight away in his barge to see Jane Seymour, and their engagement was announced the next day. Ten days later they were married and she took up her official position of Queen on this day. It has to be one of the quickest romances in history - just over one month between the two Queens.

Whilst I sip my champagne and tuck into cake, Queen Jane may have celebrated becoming Queen with the tudor equivalent of champagne and cake - "Court Sops," a sort of bread and butter pudding made with bread and ale:

Take ale and sugar and nutmeg and boile it together, and then have manchet cut like tostes and then put them in the ale one by another,then boile it till the sops bee dry, straw some butter and sugar and nutmeg on it, and so serve it when it is somewhat cold.

Hmm. Think I'll give that one a miss.

Queen Jane's reign was short, as she died after childbirth only a year later and she was swiftly followed by three more wives. She had only a brief moment in the spotlight, and likewise I am snatching my brief moment of fame, before other historical belles and beaus take my place with their exciting news and new releases.

My book, The Lady's Slipper , set not in the reign of Queen Jane, but in rural England just after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, is available now. It is a love story featuring early Quakers, a rare wild flower, and a murder! Curious? You can find out more about it on the Macmillan New Writers website. UK readers - for a chance to win a copy click here.

My book, The Lady's Slipper , set not in the reign of Queen Jane, but in rural England just after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, is available now. It is a love story featuring early Quakers, a rare wild flower, and a murder! Curious? You can find out more about it on the Macmillan New Writers website. UK readers - for a chance to win a copy click here.

Cheers everyone!

But on this date, the 4th of June, 474 years ago Jane Seymour was enthroned Queen of England after a whirlwind engagement and speedy marriage to Henry VIII. Ann Boleyn was beheaded on the 19th May, and Henry wasted no time - he set off straight away in his barge to see Jane Seymour, and their engagement was announced the next day. Ten days later they were married and she took up her official position of Queen on this day. It has to be one of the quickest romances in history - just over one month between the two Queens.

Whilst I sip my champagne and tuck into cake, Queen Jane may have celebrated becoming Queen with the tudor equivalent of champagne and cake - "Court Sops," a sort of bread and butter pudding made with bread and ale:

Take ale and sugar and nutmeg and boile it together, and then have manchet cut like tostes and then put them in the ale one by another,then boile it till the sops bee dry, straw some butter and sugar and nutmeg on it, and so serve it when it is somewhat cold.

Hmm. Think I'll give that one a miss.

Queen Jane's reign was short, as she died after childbirth only a year later and she was swiftly followed by three more wives. She had only a brief moment in the spotlight, and likewise I am snatching my brief moment of fame, before other historical belles and beaus take my place with their exciting news and new releases.

My book, The Lady's Slipper , set not in the reign of Queen Jane, but in rural England just after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, is available now. It is a love story featuring early Quakers, a rare wild flower, and a murder! Curious? You can find out more about it on the Macmillan New Writers website. UK readers - for a chance to win a copy click here.

My book, The Lady's Slipper , set not in the reign of Queen Jane, but in rural England just after the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, is available now. It is a love story featuring early Quakers, a rare wild flower, and a murder! Curious? You can find out more about it on the Macmillan New Writers website. UK readers - for a chance to win a copy click here. Word addict, book addict. Nature, art and poetry fan, and writer of thought-provoking historical fiction, published by Macmillan/St Martin's Press/Endeavour Press

Creative writing tutor and writing mentor.

www.deborahswift.com

@swiftstory

Word addict, book addict. Nature, art and poetry fan, and writer of thought-provoking historical fiction, published by Macmillan/St Martin's Press/Endeavour Press

Creative writing tutor and writing mentor.

www.deborahswift.com

@swiftstory

Tuesday, June 1, 2010

Women, Alchemy and 'A Knight's Enchantment'

Everyone knows that alchemy is the art of turning base metals into gold. It was also seen as a pursuit of divine knowledge and immortality. From its very beginning in the ancient world, alchemy was seen either as a glorious search for truth or as a means for charlatans to hoodwink money out of gullible patrons. Such dabblers in the art were known unkindly as 'puffers' - from the bellows often used in alchemy in the heating of substances - and were despised by the more serious students of alchemy.

Everyone knows that alchemy is the art of turning base metals into gold. It was also seen as a pursuit of divine knowledge and immortality. From its very beginning in the ancient world, alchemy was seen either as a glorious search for truth or as a means for charlatans to hoodwink money out of gullible patrons. Such dabblers in the art were known unkindly as 'puffers' - from the bellows often used in alchemy in the heating of substances - and were despised by the more serious students of alchemy.In my new book, A Knight's Enchantment, the heroine, Joanna, is an alchemist. From earliest times, when the strange ‘science’ of alchemy developed, women became alchemists. They were as respected as men in this profession and several were particularly revered. Many powerful and influential women studied alchemy, including the countess of Pembroke Mary Sidney, Queen Christina of Sweden and even Marie Curie.

Why were women drawn to alchemy? Famous and successful alchemists tended to be long-lived - usually far longer than the average life-span. That and the prospect of riches may have drawn some, though alchemical thinking also attracted the religious and mystical such as Hildegard of Bingen. In part, too, women may have been intrigued by alchemy because they were accepted and respected in it. The feminine principle was acknowledged in alchemy - many saw nature itself as female and today doctors still used the alchemical symbol for copper, a soft, malleable metal, for woman.

Why were women drawn to alchemy? Famous and successful alchemists tended to be long-lived - usually far longer than the average life-span. That and the prospect of riches may have drawn some, though alchemical thinking also attracted the religious and mystical such as Hildegard of Bingen. In part, too, women may have been intrigued by alchemy because they were accepted and respected in it. The feminine principle was acknowledged in alchemy - many saw nature itself as female and today doctors still used the alchemical symbol for copper, a soft, malleable metal, for woman.Women were also given credit for their alchemical work and inventions. One of the most famous, called the 'Mother' of alchemy, was Maria the Jewess, who lived in the first or second century AD, possibly in Alexandria. She recognized the importance of changes in color in chemical and alchemical reactions and is credited with inventing a still used for distillation and also the balneum mariae (bain-marie); a water bath that is kept at a constant heat via a kettle or cauldron. A contemporary of Maria was Kleopatra, who likened the growth and progress of alchemical work to a baby growing in a womb.

Women could also be married to alchemists and help them in their work. Nicholas Flamel, a famous medieval alchemist who lived for a time in Paris, was assisted in his work by his wife Perenelle and, when their experiments in alchemy brought them wealth, they jointly founded hospitals.

Women could also be married to alchemists and help them in their work. Nicholas Flamel, a famous medieval alchemist who lived for a time in Paris, was assisted in his work by his wife Perenelle and, when their experiments in alchemy brought them wealth, they jointly founded hospitals. When so many professions were closed to women in the past, perhaps it is not surprising that some chose to pursue this most secret and at the same time most fascinating of arts.

A Knight's Enchantment is published today, June 1st. Details and an excerpt are here.

Lindsay

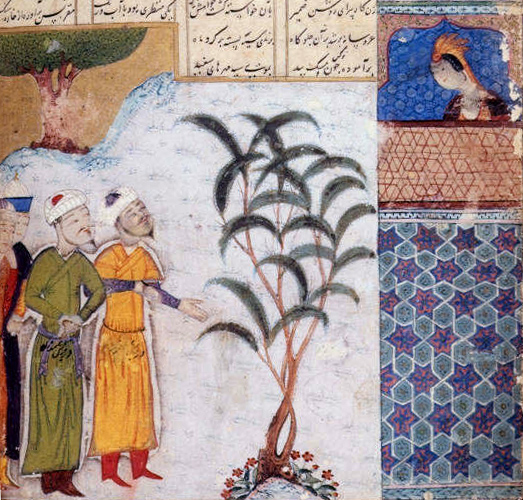

[Colour picture from The Alchemy Website, others from Wikimedia Commons.]

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)