I’ve always loved fairy tales: African fairy stories, Old Peter’s Russian tales, Grimm’s fairy tales and the western classics – Cinderella, Sleeping Beauty, Beauty and the Beast, The Goose Girl, The Frog Prince. The themes of love, sacrifice, keeping promises (the theme of the Frog prince) transformation (in The Goose Girl and Cinderella) justice (again in Cinderella) are epic to me and timeless, worthy of exploration in romances and modern stories.

Cinderella, the story of selfless devotion rewarded, is a popular theme for many romance stories, with the ‘prince’ often an Italian or Arab billionaire who sweeps in to transform the heroine’s drab, oppressed life. I’m sure there are romances to be written about the ugly sisters, too – positive stories where they grow from their petty spitefulness and obsession over balls and dances into generous, complete women, who also find love. That element of the happily ever after and the unexpected is strong in both fairy tales and in romance and both appeal to me greatly.

Fairy tales can also be epic, dealing with issues of life and death. Look at Gerda and her determination to win her brother out of enchantment in The Snow Queen. Look at Sleeping Beauty, where the prince rescues the princess from the ‘death’ of endless sleep.

Recently I did my own ‘take’ on Sleeping Beauty in my ‘A Christmas Sleeping Beauty’. I made it a story of transformation for both my heroine, Rosie, and the prince Orlando, who starts as a very arrogant and selfish young man who needs to learn to love and cherish. I didn’t want my Rosie to be passive, simply waiting to be woken, so she is active in the story both through her dreams and through her speaking directly to the hero in a letter. I also added more urgency by making it a ticking clock story – Orlando must wake Rosie in three days or he loses his chance forever.

The story of Beauty and the Beast has thrilled me since I was a child, with its dark and menacing beginning, the terrifying beast and Beauty’s courage and love for her father and ultimately for the beast. I was inspired by these basic tenets to write my own medieval version of Beauty and the Beast in my ‘The Snow Bride’. Magnus, the hero, has been hideously scarred by war and looks like a beast. He considers himself unworthy of love. Elfrida, my heroine, is also an outsider since she is a white witch, but she willingly sacrifices herself (as Beauty does in the fairy story) because of love, in her case her love for her younger sister, Christina, for whom she feels responsible. When she and Magnus encounter each other, I made it that they could not understand each other at first, to add to the mystery and dread – is Magnus as ugly in soul as in body? They must learn to trust each other, despite appearances, and come to love (just as in the original fairy tale).

I also added other fairy tale elements to ‘The Snow Bride’: magic, darkness, the idea of three (a common motif in fairy tales) spirits in the forest and more. Perhaps in the darker elements of my forest I was inspired by that other old fairy story – Red Riding Hood.

How about you? What inspires you in your reading or writing?

Lindsay

http://www.lindsaytownsend.net

http://www.twitter.com/lindsayromantic

Showing posts with label The Snow Bride. Show all posts

Showing posts with label The Snow Bride. Show all posts

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Thursday, December 29, 2011

Rites of Winter - Medieval Christmas Revels

By Lindsay Townsend

By Lindsay TownsendMake we mery, both more and lasse,

For now ys the tyme of Chrystymas

(From a 15th century carol)

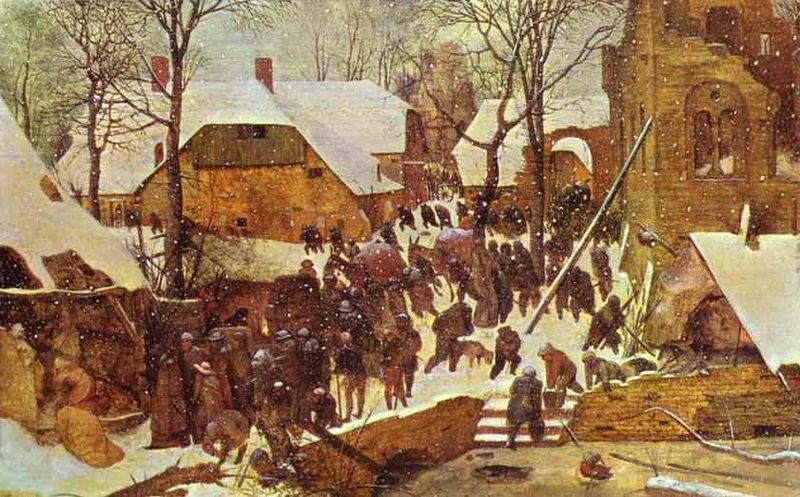

When Christianity developed in the ancient Roman world, the winter solstice was already marked at 25th December. Followers of Mithras believed in the ‘unconquered sun’ and also held a feast-day for the sun on December 25th.

The gospels did not give a date for the birth of Jesus, but ancient beliefs in the Roman Saturnalia, the solstice and sun-worship led to the church choosing December 25th as the time of his nativity.

‘Christmas’ means ‘Christ’s Mass.’ In England in the Middle Ages three masses were celebrated on December 25th - the Angel’s Mass at Midnight, the Shepherds’ Mass at dawn and the Mass of the Divine Word during the day.

Before the three masses of Christmas there was the forty days of Advent. Advent was similar to lent, a time of spiritual reflection and preparation for the coming of Christ. Feasting and certain foods such as meat and wine were meant for be abstained from during advent (something the evil Denzils ignore in my historical romance The Snow Bride, set at this time).

The feasting and revelling time of medieval Christmas began on Christmas Eve and lasted 12 days, ending on Twelfth Night. There was no work done during this time and everyone celebrated. Holly, ivy, mistletoe and other midwinter greens were cut and brought into cottages and castles, to decorate and to add cheer.

The most important element of the revels was the feast. Christmas feasts could be massive – Edward IV hosted one at Christmas in 1482 when he fed and entertained over two thousand people. For rich medieval people there was venison or the Yule boar, a real one, and for poorer folk a pie shaped like a boar, or a pie made from the kidney, liver, and other portions of the deer (the umbles) that the nobles did not want – to make a portion of ‘umble pie'. Carefully hoarded items were also brought out and eaten and other special Christmas foods made and devoured. Mince pies were made with shredded meat and many spices. ‘Frumenty,’ a kind of porridge with added eggs, spices and dried fruit, was served. A special strong Christmas beer was usually brewed to wash all this down, traditionally accompanied with a greeting of 'wes heil' ('be healthy'), to which the proper reply was 'drinc heil'.

There were also other entertainments apart from eating and drinking – singing, playing the lute or harp, playing chess, cards or backgammon and carol dancing.

Presents and gift giving was originally not part of Christmas but of New Year. Romans gave gifts to each other at Kalends (New Year) as well as a week earlier at Saturnalia, and by the twelfth century it seems that children were already receiving gifts to celebrate the day of their protecting saint, St. Nicholas, and the practice soon began to extend to adults as well, initially as charity for the poor. As the Middle Ages wore on, the custom grew of workers on medieval estates giving gifts of produce to the estate owner during the twelve days of Christmas - and in return their lord would put on all those festivities.

Wes heil!

Lindsay Townsend

http://www.lindsaytownsend.net/

For now ys the tyme of Chrystymas

(From a 15th century carol)

When Christianity developed in the ancient Roman world, the winter solstice was already marked at 25th December. Followers of Mithras believed in the ‘unconquered sun’ and also held a feast-day for the sun on December 25th.

The gospels did not give a date for the birth of Jesus, but ancient beliefs in the Roman Saturnalia, the solstice and sun-worship led to the church choosing December 25th as the time of his nativity.

‘Christmas’ means ‘Christ’s Mass.’ In England in the Middle Ages three masses were celebrated on December 25th - the Angel’s Mass at Midnight, the Shepherds’ Mass at dawn and the Mass of the Divine Word during the day.

Before the three masses of Christmas there was the forty days of Advent. Advent was similar to lent, a time of spiritual reflection and preparation for the coming of Christ. Feasting and certain foods such as meat and wine were meant for be abstained from during advent (something the evil Denzils ignore in my historical romance The Snow Bride, set at this time).

The feasting and revelling time of medieval Christmas began on Christmas Eve and lasted 12 days, ending on Twelfth Night. There was no work done during this time and everyone celebrated. Holly, ivy, mistletoe and other midwinter greens were cut and brought into cottages and castles, to decorate and to add cheer.

The most important element of the revels was the feast. Christmas feasts could be massive – Edward IV hosted one at Christmas in 1482 when he fed and entertained over two thousand people. For rich medieval people there was venison or the Yule boar, a real one, and for poorer folk a pie shaped like a boar, or a pie made from the kidney, liver, and other portions of the deer (the umbles) that the nobles did not want – to make a portion of ‘umble pie'. Carefully hoarded items were also brought out and eaten and other special Christmas foods made and devoured. Mince pies were made with shredded meat and many spices. ‘Frumenty,’ a kind of porridge with added eggs, spices and dried fruit, was served. A special strong Christmas beer was usually brewed to wash all this down, traditionally accompanied with a greeting of 'wes heil' ('be healthy'), to which the proper reply was 'drinc heil'.

There were also other entertainments apart from eating and drinking – singing, playing the lute or harp, playing chess, cards or backgammon and carol dancing.

Presents and gift giving was originally not part of Christmas but of New Year. Romans gave gifts to each other at Kalends (New Year) as well as a week earlier at Saturnalia, and by the twelfth century it seems that children were already receiving gifts to celebrate the day of their protecting saint, St. Nicholas, and the practice soon began to extend to adults as well, initially as charity for the poor. As the Middle Ages wore on, the custom grew of workers on medieval estates giving gifts of produce to the estate owner during the twelve days of Christmas - and in return their lord would put on all those festivities.

Wes heil!

Lindsay Townsend

http://www.lindsaytownsend.net/

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)